It feels almost arrogant to start a blog by essentially saying everything you know is wrong. Oh well. The long-form title ought to be:

‘Seek permission, not forgiveness: why the web’s fundamental axioms break down when data gets personal’

but that’s a title built for an academic paper, not a blog post.

Backstory

I’ve been thinking for a while about the dynamics of online consent: what we’re saying when we say ‘yes’ or ‘I accept’ on a site — or, more often than not, ‘oh, sod it, life’s too short to read the Terms of Service’. Three distinct but related events over the past two weeks helped crystallise things, particular on how the principles that underpin the technological loveliness of web[ohgod]-2.0 go pear-shaped when they lay their paws on the data we hold dearest.

First, Tom Coates had a Howard Beale moment [artist’s reconstruction] over an inbox perennially glutted with press releases. Apparently, lots of PR types had collectively decided that being a long-standing, well-read blogger made Tom a Key Leading Influencer; or, to be more precise, someone back in the day stuck his name and email address into an industry database, and once you’re in the database, it’s assumed that you’ll appreciate cheery PR circulars into the grave. By suggesting otherwise, I’m sure that Tom has become, in the eyes of some marketeers, a rare and elusive demographic quarry, having tagged himself as a Key Leading Mardy Bastard.

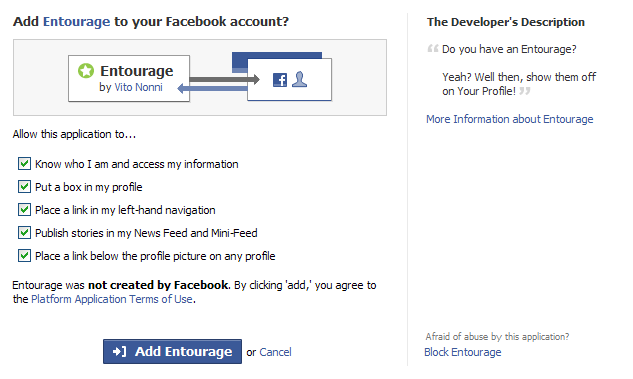

Then I logged into Facebook, for the first time in perhaps a month, to see a list of teasing notifications from contacts, all tied to various third-party applications.

Let’s get this out there: I don’t like Facebook Apps one bit, because they usually demand an uncomfortable degree of reciprocity from users on the receiving end. The most familiar example is ‘My Questions’, which was initially set up so that answering someone else’s question forced you into asking your own, usually the generic ‘What are you doing this weekend?’ This was recently fixed, or rather kludged, to allow you to answer questions without asking them, but too many apps still bring out this kind of internal dialogue:

– Ooh, I’ve been left a notification by Jane Doe, who I haven’t seen in ages. That’s cool.

– Ah. There’s a catch. To see what she said about me, I have to install an application and put another thing on my profile that I don’t really want.

– Oh well, I suppose it can’t be too–

– What are all these checkboxes for? What exactly am I consenting to? What’s the minimum I need to accept in order to see this one little thing?

– Sod this for a lark. [clicks ‘Cancel’]

– Bugger. The notification’s gone. Hm. Does Jane get notified about this? Is she going to think I snubbed her? Do I look like some kind of glorified techno-snob because I didn’t sign up for this stupid app? Grr.

There’s enough angst associated with using Facebook without it being generated by the damn backend.

Finally, along came Quechup to seal the deal, taking advantage of users’ tendency to ignore the small print in order to take their webmail address books and spam every. single. contact. The virus-like propagation of Quechup invite-spam can be dumped into the bitbucket; the embarrassment it’s caused some of the savviest people I know is harder to get over.

So, to the point. However you care to define Web 2.0, it involves large sets of user-contributed data, and web APIs to spread it around, with the aim of producing tasty mashed-up results. Now, one of the modern mantras among people working in this particular field is ‘Seek forgiveness, not permission’: if you’ve worked out how to do something funky with a particular dataset, JFDI and clean up when you’re finished.

That’s fine when you’re working with public data, abstract data, data without a pulse: some of the best examples come from people I respect most in the business. It’s that cavalier attitude that has pushed the boundaries of public service websites (in ways that the obligation-bound BBC can’t match) and which now allows Google-YouTube to peel off $100,000 bills to placate the big media corporations. But the moment you leave the public sphere, seeking after-the-fact forgiveness isn’t good enough. If that first apology comes before the angels have rained down sweet cash upon you, please pack up and find new jobs before we hunt you down with sticks.

The same inversion applies to Postel’s Law, or at least to modern interpretations of the robustness principle. ‘Be conservative in what you send, and generous in what you receive’ holds true when you’re designing a web API, just as it does for a mail server. But structures that are robust and graceful in handling data in the abstract — data treated as if it lacks a pulse — break down, very palpably, at the first breach of trust. Anyone stung by Quechup will think twice about webmail scraping from now on, even if it’s done by a site run by friends. That’s a good thing. It’s better to warn me now, gracefully or otherwise, rather than embarrass me later.

The thinky bit

danah boyd’s 2004 Etech presentation, ‘Revenge of the User’, covered some of the key sociological issues facing social networks, some time before MySpace and Facebook emerged to trample over their predecessors. She’s done plenty of compelling research since, but the creators of Facebook apps could learn a lot from this one piece. In summary,

- Articulating relationships online — and, by extension, revealing personal data about yourself — can be uncomfortable.

- People aren’t good at systematising their relationships to fit a backend model.

- Not all relationships are bi-directional, and even those with reciprocity aren’t symmetrical. Asking a question is different from answering one. Acknowledging something said by someone else is different from being the initiator.

In short, when programmatic structures and expectations bleed into the social domain, things quickly get uncomfortable.

At the time, I asked danah whether we might learn something from BDSM and the safe word, using programmatic means to define the acceptable limits of interactions. That’s the ask-forgiveness approach: consent is implied until it’s explicitly revoked. Looking back, I realise that approach fits better with the inpromptu, unstructured interactions of email and IM, where the combination of a controlled interpersonal dynamic (usually one-on-one) and an open communicative space allows for flexibility and nuance. You can talk business to one contact and talk dirty to another — or combine the two, if you’re so inclined — because interactions are, barring misclicks, segregated from person to person.

In the domain of web apps, a better model (for now, at least) may well be the infamous and much-maligned Antioch College Sexual Offense Prevention Policy:

- Consent is required each and every time there is sexual activity.

- All parties must have a clear and accurate understanding of the sexual activity.

- The person(s) who initiate(s) the sexual activity is responsible for asking for consent.

- The person(s) who are asked are responsible for verbally responding.

- Each new level of sexual activity requires consent.

- Use of agreed upon forms of communication such as gestures or safe words is acceptable, but must be discussed and verbally agreed to by all parties before sexual activity occurs.

- Consent is required regardless of the parties’ relationship, prior sexual history, or current activity (e.g. grinding on the dance floor is not consent for further sexual activity).

- At any and all times when consent is withdrawn or not verbally agreed to, the sexual activity must stop immediately.

- Silence is not consent.

It’s time to reassess just what users mean when they give consent, and what that consent is taken to mean by those who run social networking sites. It’s time to spell out the difference between permission and permissiveness.

This isn’t going to go away, as our online spoors create an ever-widening dataset to crunch. But the current generation of SNSes have failed to make significant advances over their predecessors, even at the most reputable end of the spectrum: the technology underpinning Facebook’s expansion, and thus its perceived social and commercial value, actually represents a backward step from its initial positioning as a tightly-controlled social environment.

So, perhaps it’s time for a new axiom:

The more permissive an API’s reach in terms of personal data, the more important it is to seek permission in specific, explicit, discrete instances for access to that data.

Will there be sites that seek a lucrative position outside these lines? For sure. But establishing what’s permissible will help clarify what’s meant by consent, and highlight those who betray it, outside of those excruciating moments when the parameters of permission are violated.