While I’m clearing my desk: although I love Cory and the work he does, I think I got slightly the better of this argument.

It took a couple of years to test that intuition: I waited partly for the display, partly for decentish cameras, but mainly for the point at which the iPad made sense as a solitary device, untethered from a computer for sync and management. I took the plunge last Christmas, spent Boxing Day taking my parents on a FaceTime tour of the house and garden, and got the chance over the summer to provide some onsite support.

What has my dad got out of having an iPad? Well, he’s bought parts for his lovely old banjo to restore it back to its original condition, and established its age thanks to the work of others in gathering up serial numbers; he’s restored another banjo that had been boxed up in pieces for ages, and identified it as a rare model from the 1890s. I’ve pointed him to YouTube clips of the 1960s folk revival, reminding him of the days when he was learning to play and in the audience, and he’s asked me to seek out teaching videos based on other clips he discovered for himself. He devours documentaries on the BBC iPlayer; he sketches with Paper. We still end up talking over the phone rather than FaceTime or Skype, and he’ll call up a shop rather than order online, but that doesn’t bother me one bit.

His aversion to computers has always been grounded in the fear that he’ll get lost in the UI and end up making changes that can’t be reset. For the most part, the home button deals with that.

The places where he’s struggled weren’t ones I expected, but immediately made sense. The strong Apple ID password I set up before my parents opened the box didn’t last a month. For me, a password prompt is a ten-second punctuation; for my dad, it was an impassible obstacle: switching between modes on the soft keyboard with no persistent feedback from the input box meant failure after failure, at which point the password recovery system kicked in. We worked around this by softening the password one character at a time, down to a narrow compromise between validity and comfort; once that was done, we made sure the account didn’t have any payment methods linked to it. In practice it means no app purchases, and as little authentication as possible.

This isn’t just a problem for older users getting to grips with computers and passwords: it’s increasingly obvious that strong password authentication is a mess on devices with small screens, modal keyboards and a sandboxing policy that won’t permit a password manager (or a keylogger) to loiter in the background. I’d also guess that Apple has amassed sufficient data on password strength and login failures to treat this as a problem, particularly for iCloud and the app ecosystem.

When the first leaks appeared about a fingerprint sensor on the new iPhone, many people rightly pointed out long-standing concerns with biometric authentication: the risk of central storage, reverse-engineering the source data from the stored record, but most critically, the fact that you can’t revoke your body. That leads to broader civil liberties issues about the right to avoid self-incrimination, or the use of fingerprints under duress or without consent from a overpowered, sleeping or drugged user.[1]

And yet, most reviewers of the iPhone 5S have remarked that once you spend any time using Touch ID, other iOS devices seem broken for lacking it. That’s the mark of a feature with heft and traction. I’m no less impressed with Windows 8’s picture password, which is a clever and humane way to deal with the same problem, but that’s a limited implementation: drawing bunny ears on a photo of your child isn’t going to be sufficient to authorise a payment, at least not for a little while.

The use of Touch ID for iTunes and App Store purchases is significant, and seems designed to nudge users into becoming more actively engaged with the broader iOS ecosystem. I’d now bet strongly that fingerprint sensors will appear on every new iPad launched in the coming month, because tablets are more explicitly ‘first devices’ or PC replacements than smartphones, and used more at home than elsewhere. The cost of the sensor becomes less of an issue if its presence can convert enough password-averse users into app and media purchasers: should it appear, it will be the first hardware feature from Apple in many years that could be seen as a loss-leader.[2] Tim Cook hints at this in his Bloomberg interview, in his repeated emphasis upon user engagement over raw sales numbers — ‘[d]oes a unit of market share matter if it’s not being used?’ — while noting that ‘the first time that you buy something with your finger, it’s pretty profound.’

‘Profound’ is an interesting word. It has similar roots to the Jobsian ‘awesome’, but carries more of that past with it: profound things pose questions. In that vein we ought to pose a few, because Touch ID is a microcosm of the post-PC era’s key dilemma: a feature that’s a genuine security benefit for many users, but raises equally genuine concerns about broader privacy. What is being given up in the shift towards intimate computing, tightly-integrated platforms and ubiquitous web services? What are the costs of end-user simplicity, and do they outweigh the value of end-user complexity?

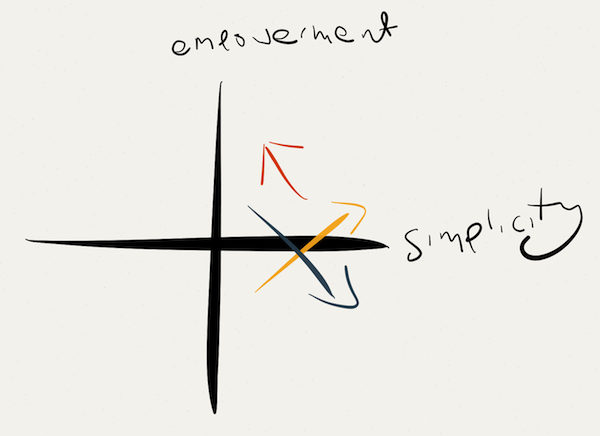

That takes us back to the original argument about the iPad, and whether its model of control empowers or disempowers users. The accurate answer, after a couple of years to judge? Both, but it’s not distributed evenly, and that distribution reflects how ‘users’ is no longer a meaningful category. It would be nice if ‘simplicity’ and ’empowerment’ had a neat correlation, but they don’t, so we need to plot it on two axes, with vectors not points, starting from an origin that differs from user to user.

I offer up this pisspoor attempt in the stratechery style:

The motivation behind Touch ID, touchscreen interfaces and most phone/tablet UI concepts is an empowering simplicity — unless you’re worried about your thumb being forcibly shoved onto a home button, value the interoperability of PC applications, or want the flexibility of a standard filesystem, in which case the simplicity is disempowering. The motivation behind teaching people to code, or hardware hacking, is an empowering complexity, but ‘coding makes you free’ or ‘you have the tools, learn to build it yourself’ are disempowering shrugs: we shouldn’t ever forget that coding is a complex activity, even as we build tools and practices to make it more accessible.

There’s always been a push-pull here between two desires: to strip away complexity so that people are comfortable with computing, and to make people comfortable with the complexity that computing allows. It’s often treated as zero-sum: in the context of hacker culture, every move towards simplicity is a portent of the impending emasculation[3] of general-purpose computing, and it’s easy to knee-jerk the other way and wish the hackers would just stop whining. My knee is no stranger to that. But as much as I increasingly want to focus on the productive, creative use of computers beyond the productive, creative use of computing, I’m mindful that what underpins that empowering simplicity is the empowering complexity of designers, engineers and coders at the top of their game.

It’s something that Craig Federighi picks up on in his Bloomberg interview:

[S]o many of the people here are so capable of dealing with complexity, so capable of operating complex tools that something could be simple, or at least workable in their eyes because of their capabilities, but that wouldn’t be very appropriate for the average person. And yet our best people, despite their own facility for navigating complexity, also have a natural gravitational pull toward simplicity and understanding what’s intuitive and continually returning to those solutions.

In my hackerish youth, when compiling Linux kernels was somehow a leisure activity, I’d probably have treated that reference to ‘the average person’ as either condescension or a threat to overrun the fiefdom. Now, I ask: who is empowered by these changes, and who is disempowered? The reckoning isn’t simply utilitarian: the next wave of empowering simplicity will be created by those who have mastered complexity, as long as they continue to have the tools to do so at their disposal.

Simple things are carved out of complex things, and those simple things can be used to build complex things that make possible other simple things. And complex things. That’s the virtuous cycle of continuous, expanding empowerment that we need to protect, the one that makes it possible for my dad to read this.

Not that he will, though: he’s got far better things to be doing with his iPad.

::

[1] I suppose I should direct a golf clap at CCC, who have ‘broken’ Touch ID with the aid of a high-resolution camera, a high resolution scanner, some transparent sheeting and wood glue, all of which are apparently ‘everyday household items’. I’m not even going to nitpick the methodology; the point about fingerprint authentication on phones and tablets is that it is functionally better than the alternatives in the majority of cases, and if you feel like you’re a target for that kind of Mission: Impossible shit, then you’ve probably already memorised a 15-digit passcode and a strong password. As the old chestnut goes, it’s not about outrunning the bear, but the other bloke it’s chasing. Questions about self-incrimination and access under duress are more troubling, and will quickly become the main focus of discussions about biometric auth.

[2] Marco Arment thinks that the gig is up for paid-up-front apps on iOS, and he’s in a massively better position than me to make that call. If that’s the case, and his subsequent posts make it seem so, then Touch ID still gets users over the hurdle of installing them and making in-app purchases. I’d love to know how many iPads don’t have any third-party apps installed; Apple certainly does know.

[3] Word choice very much intentional.