Those great concerts that stay with you, the ones that become part of who you are, resurface in fragments scattered across the senses: a single chord, a snapshot of the stage committed to memory with a blink, a whiff of dry ice as it hits the back of your throat, and above all the thrum in your chest when you leave the venue, look back and think to yourself: damn, that was a night.

You don’t expect to get that rush from a tech conference.

This month was the tenth anniversary of Emerging Tech 2004. We had a sense it was special at the time, but hindsight makes it increasingly obvious how significant it was, to be ranked alongside the blogging-era SxSW Interactive, back when most of the attendees could fit into Bruce Sterling’s house, as opposed to spilling over into Oklahoma. Except this one I was lucky enough to attend.

For context: after the dot-com bubble burst, as imaginary money vanished and real money got stuffed in mattresses, there was a retrenchment: in the UK and Europe, academia and quasi-academic institutions like the BBC served as a kind of safe harbour where it was possible to make a living and produce innovative tech without worrying about burn rates and coming in one day to find the Aerons repossessed, not least because the BBC didn’t do Aerons. Too much of that work foundered for other reasons, but that’s another story, and not mine. In North America, the stepping-back and reckoning took place out of the commercial glare, as blogging took hold and people began building creative extensions upon the structures that reinforced its organic connectedness. By 2004, the war in Iraq also impinged upon things, and the military presence at ETech took many by surprise; the awkward segue from Roomba to PackBot feels like an early hint of the era of the drone. These days we have a clearer, if gloomier sense of how innovation can be repurposed in both directions.

The highlight that everyone remembers was the launch of Flickr, one of the first of its kind and the first to go big; it now exists more as a peg on which to hang internet reckons than a place to share photographs, which is why I’ll skip it except to say that Ludicorp’s talk on ‘transcendent interactions’ feels especially poignant having seen Glitch arrive and say goodnight. Eventually Stewart and Cal and Eric and their team will build that damn game and make it last, even if it takes another few iterations of spinning off really nice non-gamey things for cash and prizes.

[A late update: it was amiss of me to neglect Findery, which sustains the whimsical, playful sensibility of GNE by inscribing memories on maps; I don’t give it enough attention, perhaps because I don’t get out enough.]

It also saw the unveiling of Life Hacks, which like too many things on the internet evolved into a morass of wrongheaded obsession, gear-driven oneupmanship and competing bullshit orthodoxies that drove its most prominent advocates to torch and flee the place. To this day, Danny denies being a stealth agent for the stationery industry.

But there are other things I take away from those few days, as both treasured memories and continual reference points for how I approach the web today. Here are a few:

danah boyd, ‘Revenge of the User’ (summary)

danah now has a decade of hugely impressive work, grounded in sleeves-rolled-up research and guided by a deep understanding of social theory (buy her book, or at very least, read it) but this early talk doesn’t feel dated at all: it lays out the gaps between social structures and ones engineered online to accommodate them, the difficulty of handling asymmetrical relationships, and the urge to expand online social networks up to the point where they become brittle. It anticipates the way in which engineering decisions have social consequences, well ahead of the emergence of MySpace or Facebook or Google+. ‘The technology will not solve the social, but each design decision made in the technology affects the social.’ I go back to danah’s work for good reasons.

Michael Kieslinger and Molly Wright Steenson, ‘Fluidtime’ (slides)

Although Interaction-Ivrea‘s time was short, its legacy is long thanks to the quality of the work that came out of it. Everyone who was at this talk remembers the web-based system for booking time on a shared washing machine and receiving alerts when your laundry is done (which echoes forward) but the broader reflections on how scheduling becomes a moving target (and movable feast) among connected groups are no less relevant.

Chris Heathcote, ’35 Ways to Find Your Location’ (slides)

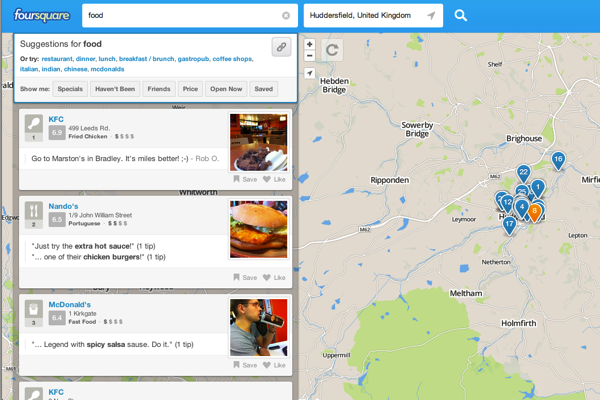

‘In 10 years’ time there will be no concept of “lost”‘ is how it begins, and while that’s not entirely accurate, it feels like an ever-shrinking terra incognita on the map. (Compare early seasons of The Amazing Race to newer ones: getting directions in unfamiliar locations with large populations is much less of a challenge, and when teams get lost, it’s often due to the artificial constraints that the producers now enforce upon teams.) Chris’s talk on the many facets of wayfinding holds value to this day; we’re already at the point of his social future in which location can be drawn from ‘who you are near’, ‘objects you are near’ and aggregated flows. (If you were on Tinder a week ago and a lot of young snowboarders showed up, chances are you were in Sochi.)

Matt Webb, ‘Glancing: I’m OK, You’re OK’ (slides and notes)

Socially ambiguous software; minimalist interaction; phatic reciprocity; subtle networked presence, analogue statefulness: I see hints of it in the ‘oh hey’ in-passing dialect of certain corners of Twitter, or in certain uses of the fave and like, and other hints of its dissemination into connected devices. The promise of the Internet of Things will depend upon its ability to glance.

As the line goes, predictions are hard, especially about the future, but perhaps what gives these talks their sticking power is how they’re not tied to specific technologies, but instead focus on human interaction. People don’t change much: if you get that part right, you’ll be forgiven for what you place on their laps or in their pockets a decade on. The stuff of technology changes quickly, but the most important questions we ask of it are the ones we ask slowly, and keep asking.

This past month also brought us Webstock, beloved of all who attend and an ongoing source of inspiration for those who watch from afar. There too, the most important questions focus on people first, and are ones we’ll likely revisit in a decade.